Railway History

BC Rail-PGE Railway brief history

A brief history of the British Columbia Railway & the Pacific Great Eastern Railway

Originally published in The Western Depot newsletter.

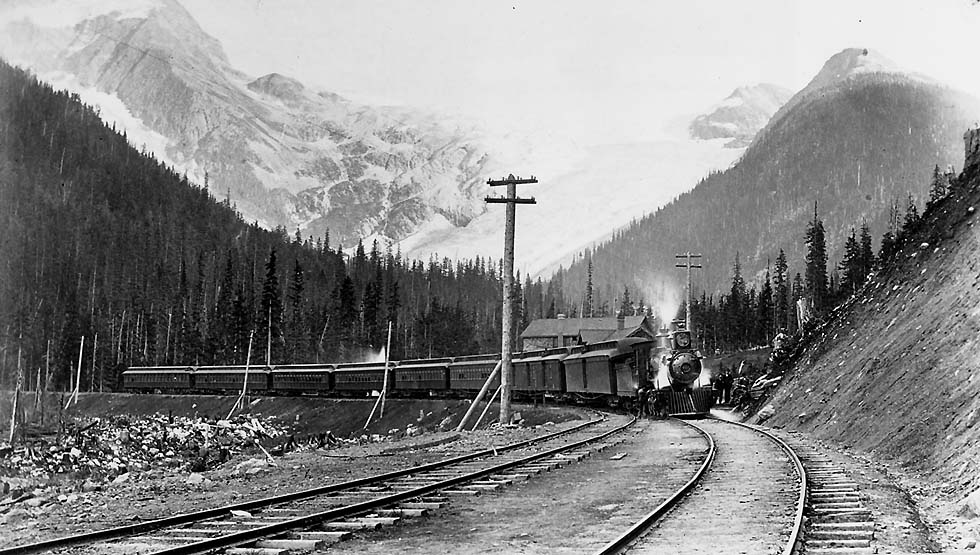

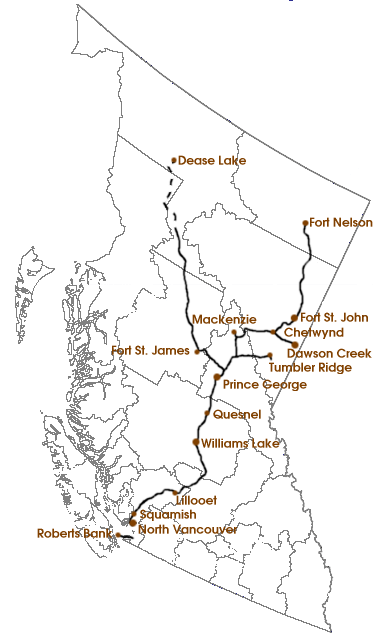

BC Rail, known as the British Columbia Railway between 1972 and 1984, and as the Pacific Great Eastern Railway before 1972, was a railway that operated in British Columbia from 1912 to 2004. At its peak, it was the the third largest railroad in Canada, operating 1,440 miles of mainline track.

![]()

BC Rail was incorporated as the Pacific Great Eastern Railway (PGE) in 1912 in order to build a line from Vancouver, BC to a connection with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway at Prince George. The PGE was provincially-sponsored, and was originally meant to unify British Columbia under one rail system. However, at it’s start it ran into much criticism, often called “the line from nowhere to nowhere” since it ran between Pemberton and Lillooet, two small communities in rural, inland British Columbia. In 1915, PGE extended the main line south to Squamish, and north to Chasm, growing the line to over 175 miles.

Also in 1915, PGE failed to make an interest payment on its bonds. This caused a legal battle between the founders of the railroad, Timothy Foley, Patrick Welch, and John Stewart, and the British Columbian government, which eventually led to the railway being be turned over to the government. At the time of the government takeover, PGE had two sections of track: one between North Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay, and one between Squamish and Clinton.

After the takeover, the government extended the railway to a point 15 miles north of Quesnel, which was later removed. For the next 20 years, the PGE did not connect with any other railway, and there were no large urban centers on its route. It mainly connected logging and mining operations of the British Columbia Interior with the coastal town of Squamish, where these resources were transported by sea. Resources were not available for the government to expand the railway to the intended target of Prince George, and to its detractors PGE came to stand for “Province’s Great Expense”, “Prince George Eventually”, “Past God’s Endurance”, and “Please Go Easy”.

Finally beginning in 1949, there were financial allocations that allowed the Pacific Great Eastern to begin to expand. Track was laid north of Quesnel to a junction with the Canadian National Railways at Prince George. Between 1953 and 1956, the PGE constructed a line between Squamish and North Vancouver. In the 1960s, the PGE was extended from Fort St. John 250 miles north to Fort Nelson.

In 1972, the PGE became the British Columbia Railway (BCR). Then in 1984, the BCR was restructured. Under this new organization, BC Rail Ltd. was formed, owned jointly by the British Columbia Railway Company and BCR Properties Ltd. At this time, the rail operations became known as BC Rail.

Still known as the BCR, the railway began to expand from Fort St. James to Dease Lake in the 1970s to take advantage of asbestos and copper in the area. However, before the line was even completed, worldwide demand for both asbestos and copper fell dramatically and the line was never finished. Construction stopped in 1977, when there had already been 263 miles of track laid. It had cost $168 million to reach that point.

Parts of the unfinished Dease Lake extension were used to serve the logging communities at Driftwood. Once logging operations ceased in 1983, traffic fell sharply and the Dease Lake line was closed.

BC Rail opened the Tumbler Ridge Subdivision to the Quintette and Bullmoose mines in 1983. This was an 82 mile electrified branch line that had the lowest crossing of the Rocky Mountains by a railway at 3,815 feet. This line ran through two large tunnels: The Table Tunnel at 5.6 miles long, and The Wolverine Tunnel at 3.7 miles long. The Tumbler Ridge Subdivision was electrified partly due to these two long tunnels, and partly due to its proximity to the W.A.C. Bennett Dam and transmission lines. This was one of the only electrified freight lines in North America.

Although initially profitable, traffic was never as anticipated. By the 1990 traffic was under one train per day. These unprofitable operations could not repay the debt incurred in building this line, and in 1984 BC Rail acquired the British Columbia Harbors Board Railway, a 23 mile line connecting three Class I railways with Roberts Bank, an ocean terminal that handles coal shipments.

Through the 1990s the provincial government reduced subsidies to BC Rail, which led to the outstanding debt growing over sixfold between 1991 and 2001. BC Rail tried to overcome the ever increasing debt by branching out into shipping operations, acquiring Vancouver Wharves in 1993 and Canadian Stevedoring in 1998. In 1999, Vancouver Wharves, Canadian Sevedoring and its subsidiary Casco Terminals were spun into a new entity, BCR Marine. In order to reduce mounting debt, BC Rail sold off the BCR Marine assets except Vancouver Wharves.

Further hardships ensued when in 2000, the Quintette mine closed and a portion of the Tumbler Ridge Subdivision was abandoned. The Bullmoose mine closed in 2003, after which the remaining 70 miles of the Tumbler Ridge Subdivision was abandoned as well. Passenger service ended in 2002 and many of the RDC locomotives used by BC Rail were decommissioned and either scrapped or sold to museums around North America. Also around this time BC Rail ended intermodal service.

On November 25, 2003, the $1 billion bid by Canadian National was accepted by the government, and operation was handed over to CN on a 60 year lease.

– republished from The Western Depot newsletter.

The Western Depot. 1650 Sierra Avenue, Suite 203, Yuba City, CA 95993-8986, 530-673-6776

CP Rail – A brief history

A brief history of the Canadian Pacific Railway

By Wesley McBratney – The Western Depot.

Published Jan 19, 2016

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) began in 1870 when British Columbia insisted upon a transport link to the East as a condition of joining the Confederation of Canada. At the same time, manufacturing interests needed access to raw materials and markets in Western Canada. The early history of CP is full of controversy, including the toppling of the Conservative government and forcing an election. This caused a stall in the project, and construction did not begin until a group of Scottish Canadian businessmen formed a syndicate to build a transcontinental railway in 1880, nearly 10 years behind schedule.

The railroad was incorporated in 1881, with George Stephen as its first president. That first year of construction was a complete bust with only 131 miles of track built. The chief engineer and general superintendent were fired and replaced by William Cornelius Van Horne. Van Horne boasted that he would build 500 miles of main line railway in his first year.

Floods delayed the start of the 1882 construction season, but by the end of the year, Van Horne had laid 418 miles of main line and 110 miles of branch line. The Thunder Bay branch was completed in June 1882 by the Department of Railways and canals and turned over to CP in 1883, permitting all-Canadian lake and railway traffic from Eastern Canada to Winnipeg for the first time in Canada’s history. By the end of 1883, the railway had reached the Rocky Mountains.

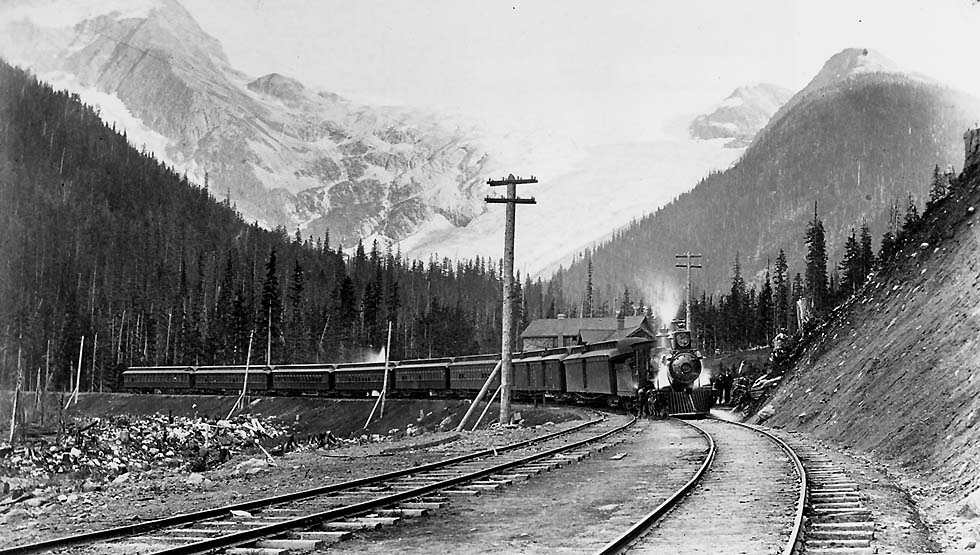

On November 7, 1885, the eastern and western portions of the Canadian Pacific Railway met at Craigellachie, British Columbia, where Donald A. Smith drove the last spike. The first transcontinental train leaving Montreal and Toronto for Port Moody left on June 28, 1886, and arrived on July 4, 1886. This train consisted of two baggage cars, a mail car, a second class coach, two immigrant sleeps, two first-class coaches, two sleeping cars, and a diner. At around the same time, the western terminus had moved from Port Moody to Granville, which was later renamed Vancouver.

By 1889, the railway extended from coast to coast and the enterprise had expanded to include a wide range of related and unrelated businesses. CP had been involved in land settlement and land sales as early as September 1881. They also erected telegraph lines along the transcontinental line, performed express shipping and built some of their own steam locomotives. CP later built its own passenger cars, making it second to only the Pullman Company in passenger car production.

CP also had steamships on the Great Lakes, chartered ships on the Pacific Ocean, and launched its own Pacific fleet in 1891. They were also involved in tourism and natural gas.

At the same time as they were diversifying, CP was also expanding their rail holdings. CP leased the New Brunswick Railway in 1891 for 991 years, and built the International railway of Maine in 1889. In 1896 the decision was made to chart a second main line across British Columbia due to pressure from Great Northern and BC Rail. One result of these new lines in the West was that CP helped settle Western Canada as they ran an intense campaign to bring immigrants into Canada. Immigrants were sold a package that included passage on a CP ship, travel on a CP train, and land sold by the CP at $2.50 an acre requiring cultivation.

During the first part of the 1900s, CP continued fast paced growth via construction and acquisitions. They built several long bridges and tunnels, extending their lines to places previously inaccessible. The CP also acquired several smaller railways during this time such as the Dominion Atlantic Railway, which gave CP a connection to Halifax for the first time. (Image: Trans Canada Limited of Canadian Pacific near Lake Louise, Alberta, c.1922. Canadian Pacific Corporate Archives)

During the First World War, CP put its entire resources at the disposal of the British Empire, including trains and tracks, ships, shops, hotels, telegraphs, and staff.

As Canada entered the Great Depression, many railroads were strongly affected. However, because it was debt free at the time, CP was largely unscathed. One highlight of the 1930s was the Royal Tour of Canada, where CP and Canadian National pulled the Royal Trains across the country. Shortly after the Royal Tour, World War II broke out.

As government energy and production geared toward World War II, CP put their entire network at the disposal of the war effort. CP moved 307 million tons of freight, 86 million passengers, including 280,000 military personnel. They sent 22 ships to war, with only 10 returning, and they pioneered the “Atlantic Bridge”, which ferried bombers from Canada to Britain.

After World War II, cars, trucks, and airplanes changed the landscape. Where rail was king, now cars, trucks, busses and airplanes took passenger and freight traffic away from the railways. CP was well situated to deal with this as they already had a hand in air and truck freight business.

In the 1950s, CP was completely dieselized. In the 1960s started to pull out of passenger service, and in 1978, they transferred passenger service to VIA Rail. By 1986, CP was Canada’s second largest company with $15 billion in revenue, including their income from CP Railway, PanCanadian energy, Fordling Coal, CP (Fairmont) Hotels, and CP Ships.

CP continued to grow with CP taking full control of the Soo Line in 1990 giving it access to the US Midwest. Soo had already absorbed Milwaukee Road and the Minneapolis, Northfield and Southern, in 1990. In 1991, CP bought Delaware and Hudson, giving it access to ports in the US Northeast.

Currently, CP holds a 14,000 mile network extending from the Port of Vancouver to the Port of Montreal, including the US industrial centers of Chicago, Newark, Philadelphia, Washington DC, New York City, and Buffalo.

Published with permission. the CTTA thanks Wesley McBratney and The Western Depot.

1650 Sierra Avenue # 203, Yuba City, CA 95993 wesley@westerndepot.com, www.westerndepot.com

Bibliography:

Berton, Pierre (2001) [1970]. The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881. Anchor Canada.

http://www.cpr.ca/en/about-cp/our-history

Dorman, Robert and Stoltz, D.E. “A Statutory History of Railways in Canada 1836-1986”. The Canadian Institute of Guided Ground Transport, Queen’s University, 1987, pp. 109-110, 213, 293, 374, 421

Shaak, Larry. “Royalty Rides the Rails: A railroading perspective of the 1939 Canada/USA Royal Tour”. Larry Shaak (2009), p. 189

CBC Digital Archives